Her magnum opus, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, was turned down by seven publishers before being accepted by Yale University Press. Its

publication initially attracted precious little attention.

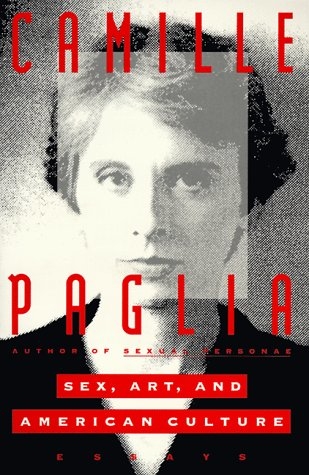

On these unpromising foundations, Paglia built a formidable media reputation, becoming the most fabled warrior in America's culture wars (Independent on Sunday), the Joan of Arc of the mavericks of us feminism, the love-to-hate-her target of the old-school feminists she seems born to affront. From academic nonentity to media megastardom, the sort of mythic, order-affronting transformation Sexual Personae is concerned with documenting. Once a loser, now prophet, pariah, and thinking-person's cover-girl, her latest book, Sex, Art, and American Culture shows how she did it.

The essays in the collection cover subjects as diverse as Elizabeth Taylor (for Playboy), Milton Kessler (her teacher) and body building. What they have in common is Paglia's snappy writing style - when aiming at a popular market - and innate quotability. More than this, they're full of her awareness that marketing techniques apply even within the realm of ideas. Paglia devotes plenty of ink to personal anecdotes designed to

reveal her rags-to-riches rise, her ambiguous sexuality (formerly a lesbian, now bisexual), her roots in the progressive sixties - the nostalgia for which she taps unmercifully in her famous mit lecture, even her (for an

academic) glamorous looks. It's pure soap opera. I inhabit television reality, she said in one of many interviews which heralded spring 1993. I have 3 tvs in my house and I'm about to get a 4th. I have them on all day. Three? Four? This is the woman so hungry for popular culture she watches four tvs at once. It's all Paglia Added Value. Buy this book, astound your friends with Camille's ideas, drop Paglia's name in conversation, feel guilty no more about watching tv.

Paglia's popularity has little to do with Sexual Personae, an unwieldy, meandering volume which over 700 pages illucidates two main arguments: one, that civilisation is the result of the triumph of the rational

Apollonian (male) ordering principle over the irrational, chaotic Dionysian (or as Paglia prefers, chthonian) forces of nature, the province of the female; two, that the inequalities between the sexes are less the result of

male oppression than of biological differences. Whereas men are driven to impose order and create pattern, women wallow in the emotive, pre-rational realm of nature, thus: If civilization had been left in female hands, we would still be living in grass huts. Paglia's murky theories of Apollonian and chthonian energy have barely been heard of since, but such phrases as the aforementioned have won her the pinnacle of celebrity.

Once in print, Paglia, aided and abetted by magazine and paper editors, sensibly set to distilling the credo of the meaty Sexual Personae into bite-sized journalistic pieces -- these are the essays collected in Sex, Art and American Culture. Her big breakthrough was the December 1990 ''New York Times' Madonna - Finally a Real

Feminist. The article championed the Material Girl as the true feminist. She exposes the puritanism and suffocating ideology of American feminism, which is stuck in an adolescent whining mode.'' La Ciccione, far from being an affront to the female sex, was an embodiment of its eternal erotic power.

It was the first time Paglia reached a wide audience, and at once a connection between herself and the subject of the piece, Madonna, was established. The two, as Paglia saw it, were engaged on the same crusade against American feminism, its denial or misreading of female sexuality and castration of all-ordering masculine power (they fear and despise the masculine. The academic feminists think their nerdy bookworm husbands are the ideal model of human manhood.)

The Paglia brand was established. As her star rose with a series of shock-tactic articles on date-rape and the deplorable state of American universities, Paglia took charge of her photo shoots, presenting herself in a series of images for which Madonna was her undoubted mentor. For the San Francisco Examiner, she posed in a mini-skirt toying with a bull whip outside a porn store. In People, she emerges from a sinister alley brandishing a flick-knife. Amazon-like she appeared with one of her two swords on the cover of New York magazine. She took to appearing in public with two towering black bodyguards. She was dubbed, the intellectual pin-up of the 90s.

In the first Madonna piece Paglia astutely threw in an aside on the date rape furor, pouring scorn on the aphorism, No always means No. Unsurprisingly, she was soon commissioned by Newsday to write an article on the controversy, which appeared in January 91. College men are at their hormonal peak... A girl who lets herself get dead drunk at a fraternity party is a fool... Aggression and eroticism are deeply intertwined. The piece is reproduced in Sex, along with transcriptions of Paglia interviewed in the storm of controversy which

followed her uncompromising piece.

Meanwhile the Paglia bandwagon rolled on. Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders came out in summer '91, an attack on American careerist, Ken-doll academics, academic feminism and French critical theory (it is revolting to see pampered American academics down on their knees kissing French bums.). In this incarnation chameleon crusader Paglia scored her biggest hit: her subsequent lecture, The Crisis in American Universities, given in September '91 at Massachusetts Institute of Technology attracted thousands and

splashed Paglia bons mots across the front pages. In the Media History of her rise and rise which Paglia has appended to Sex, she says the experience made her feel like Fay Dunaway after winning an Oscar.

In the same Media History, Paglia claims she did no marketing or solicitationfor her articles. Ideas have their own life and, when the time is right, seem to fly like the wind. Her stardom, she claims, is a manifestation of the return of the maverick as hero -- an uncharacteristic display of modesty, underplaying the ability to hard-sell personality and manipulate the mass media which she shares with the object of the two of the Sex essays, Madonna.

Paglia is, actually, as aware of her own media-friendliness as she is of the dance styles and costumes of a decade of Madonna videos. Like Andy Warhol, I have been in love with ads since my earliest childhood, she recently told Wired magazine. One of the reasons that I probably got this famous is because I think and talk in sound-bite terms. People say She promotes herself. When I was young, I thought in newspaper headline terms: Paglia Falls Off Chair. I feel totally a part of mass media. In the same interview, reporter and subject conspire to tout 'wannabee polymath' Paglia as the new Marshall McLuhan, another good piece of branding.

In case we've missed any of the performance, Paglia helpfully lists her media identities at the end of //Sex:// woman warrior, wild woman of academia, catwoman of academia, Amazon punk philosopher, feminist fatale, hit woman of academia, academic guerilla, feminist scourge, the Jerry Brown of academic feminism, malcontent of sexual politics - hear any of these out of context and 10-to-1 even a Martian would recognise a

Paglia persona. The media appearances index is a piece of patent self-promotion. Sex, Art and American Culture are, after all, the vital ingredients in advertising.