The exotic animal trade: one might not think too much of its significance to our ecosystem. Yet, it is very much “alive and kicking” and becoming a real threat in the global world. Recently, the Animal Advocacy and Protection foundation (AAP) released results of their 2019 survey (Pieters, 2019). It was stated that up to 55 breeds of exotic animals (both legal and illegal species) were marketed for sale online and offline. Sites like Marktplaats and Facebook are the most common medium for the trade, as up to 45 of the exotic breeds were advertised. Pet shops contributed less than half of that number; and animal fairs average equal to that of pet shops. But this exotic trade, as dangerous as it can be, is not one that emerged out of nowhere. It is deeply rooted in European colonial history.

It is 1703. Imagine the sight of a gigantic alien nearby the dairy market on Rembrandtplein: the length of its nose matches that of its tail, the hefty stomp of its feet echoes like tropical thunder, and the sheer size of its body can only be likened to quarried boulder. It is an Indian elephant but to a pre-modern citizen of Amsterdam, this is a sight to behold! It is an awesome exhibition, one that deserves an enormous audience, to marvel at the wonders of the East. But people have always been interested in the exotic species even before. Prior to the (Dutch) Golden Age, these animals were only available for spectacle through travelling shows. But with colonial expansion in the 17th and 18th century, it became possible to capture and exhibit these animals in Amsterdam, permanently.

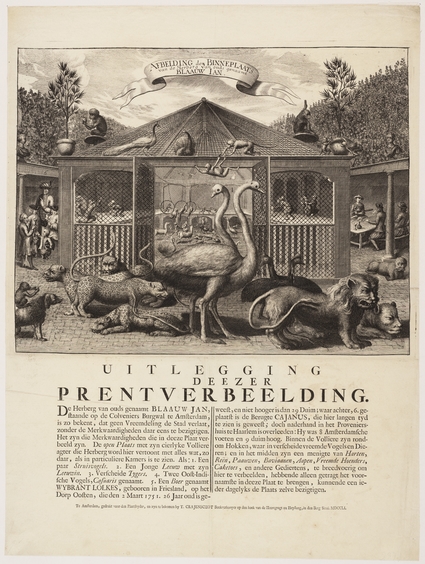

The VOC once had a commissioned business to manage and transport animals from the West and East Indies (Pieters, 2001). These ordered deliveries were for exotic species of animals intended for the elites—either as a gift between men in office or to “curious nature lovers” as they once called it. Precisely, these curios amateurs were the owners of menageries and cabinets. This meant that non-indigenous species of fauna came into the city through the port of Amsterdam and then housed close-by for exhibition. One of the few popular ones were ‘The White Elephant’ and the ‘Menagerie of Blue John’. Advertisements were often posted on the new and exciting animals to behold: such as the “Campergoo” and “Nigoms’ devil”, otherwise known today as the two-banded monitor and the Indian pangolin. Other animals also included a sea turtle weighing about 500 lbs, and a South American tapir (Pieters, 2001). And despite the fact that these menageries no longer exist, the interest in these exotic animals did not just disappear.

The Artis Zoo was established in 1838. As its own institution, the initial collection was a rather weak one. It only housed a few parrots, monkeys, and a Suriname wildcat. But, in 1839, the zoo absorbed the collection of a particular “curious nature lover”, that is C. van Aken (Artis Zoo, 2019). His menagerie was headlined by Jack the elephant and accompanied by several species of big cats, bears, snakes, and even a wildebeest. Soon after, with more collections absorbed, the Artis Zoo became a real zoo. All thanks to the efforts of the VOC ships.

There is no doubt that these collections of exotic animals were a brilliant spectacle. But it surely is nothing compared to the novel scents introduced! After all, one of the most overwhelming sensation at the zoo is the amalgam of smells emanating from each species, all to accompany the foreign view.