The main hero of the animated series Primal, created by the famed animator Genndy Tartakovsky, is a Neanderthal man with the pseudonym Spear. Throughout almost the whole first season, we never hear him speak. It is through sounds such as grunts and growls that he expresses his emotions and communicates, specifically with his comrade Fang (a T-rex). Here, it should be noted that Primal does not take place in any particular historical or geological period. Instead, Tartakovsky breaks down historical and geological timelines and brings them together to present some philosophical and historical visions regarding men, an analysis of which remains beyond the scope of this article. What is important for us is that during the first season of primal, Spear was animalized and Fang was humanized to the point that they had no need for speech to communicate with each other. Spear did not need to speak, because he had a voice, as the T-rex had a voice. And their apparent meaningless voice (meaningless since no meaningful words and discursive speech emerged from them) is the common ground on which perfectly communicable expressions could take place. However, this situation kept a question alive: could Spear speak at all? Did Tartakovsky represent him in the image of the Neanderthal as imagined during most of the 20th century, as a species of the homo genus that lacked the ability to speak? In other words, was Spear a new version of Ernst Haeckel’s Alalus?

The answer to this question is complicated, as Haeckel’s imagined Pithecanthropus Alalus is a conception of an “ape-man without speech” (Agamben, The Open 34). The term Pithecanthropus literally means ape-man, as the Latin term pithēkos stands for ‘ape’. In other words, Haeckel’s Alalus is a conception of a proto-human or a being-not-yet-men, and its lack of humanity is defined by the lack of speech. What should also be noted is that, like many of his contemporaries, Haeckel’s idea regarding the category of species was uncomfortably aligned to the idea of race. During the latter half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, “sub-species” and “race” were synonymous for many biologists (which is still true in certain branches of biology). And it must be argued that, as a metaphysical category, Haeckel’s conception of Alalus cannot be reduced to the idea of an extinct species of not-yet-men, since there were categories of men (e.g., women, natives of the colonies, black people) who had the same statues of Alalus as their political Logos and agency was not recognized under the western episteme of his time.

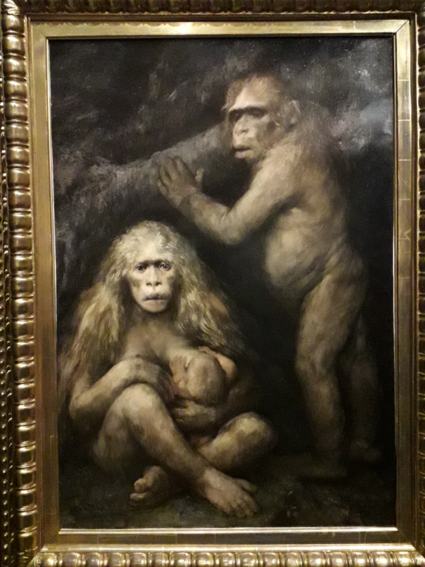

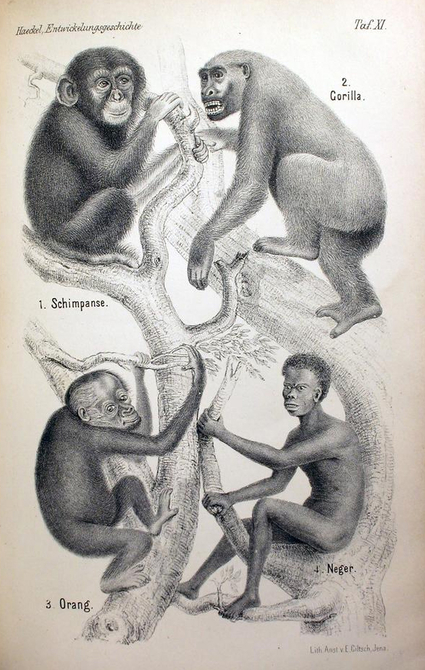

Alalus reveals a place of negativity (in relation to the legal and political discourses and practices) that could also be located in our contemporary world. Our interpretation of Alalus also provincializes the task of decentering humans in futuristic epistemologies (a task that the post-human tradition has taken as its alpha and omega), since such a task presupposes an Anthropos that has a modern western history. Slaves and natives of colonies did not have a share in such an idea of man. Haeckel’s infamous drawing of a black man along with the non-human apes is a prominent example. In this drawing, the black man is animalized to the point that we cannot imagine him having the political voice or speech of a man. It can be argued that he belongs to the category of “alalus”, or is close to this category. Haeckel was a man of his time, and was working at a time when both life science and the German philosophy of life (Lebensphilosophie) were on rise. In a world in which the demarcation between biological and social science was not yet clear, Haeckel’s social Darwinism and scientific racism were not too separated from Darwin’s thought on the evolution of human society. He struggled with the undecidability between men and animals similarly to his contemporary biologists, precisely due to the limitation of western epistemology of his time, and for being a participant in the paradoxical scientific activities in which the animalization of men and the humanization of animals were occurring simultaneously.

19th century take on racism - Haeckel's drawing on the understanding of race in his era

Post-humanism presupposes the western white men, or the idea of a man in which the black man (the so-called “Neger” of Haeckel’s drawing) or slaves did not have a place. Decentering such an idea of man, or going beyond such an idea of the Anthropos, may be necessary for contemporary western epistemology, but for the humanity that never had a place in the idea of such a humanity cannot relate with this task. From a decolonial perspective, post-human articulations are critiques of western humanism, and attempts to detach the theories of humanities and social science from the dangers of an anthropocentric worldview in which many humans were as much on the periphery as animals. Post-humanism from a decolonial perspective is thus not about decentering humans from cosmology and bringing the non-human at the center of agency. Rather, it is a theoretical struggle that decisively reckons with the undecidability between ‘men’ and ‘animal’ that is produced in every western articulation in which the identity and rights of one of these categories are at stake. For the ‘alalus’ of our time, decolonization of the western idea of men cannot be separated from the decolonization of the idea of post-human. It puts the term ‘post’ in post-human under eraser (post-human). By doing so, even though we recognize the need for the term “post” in this case, we also nonetheless make visible its contingency and groundlessness.

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben gives the name “anthropological machine” to various discursive apparatuses that produce the idea of man through the articulation of a binary between human and non-human. Anthropological machines, whether ancient or modern, also produce a place of exception, a zone of indeterminacy and indifference between the human and the animal. And the anthropological machine of the moderns often “functions by excluding a not (yet) human, an already human being from itself, that is, by animalizing the human, by isolating the nonhuman within the human” (Agamben, The Open 37). For Agamben, scientific categories such as Homo Alalus, or the political dehumanization of Jewish people are examples of the function of the modern anthropological machine in which “non-man” is produced “within the man” (The Open 37). We must, then, be aware of the risks we face in producing a new articulation of the relationship between humans and the not-human. And such awareness is specifically required if the articulation must take place with the goal of decolonizing the idea of man, since the animalization of man is also a function of the colonial form of anthropological machines (Mbembe, On The 26-27).

Agamben is concerned with the realm of pure potentiality that lies in the undecidability produced between man and animal in every articulation by the anthropological machine. The goal of this article is much more limited, but also less abstract. It has a concrete goal of gesturing towards the category of Alalus, which can be transformed into a category in which both the humans and animals (as well as the non-living) find themselves together in a common abandonment under the dominant juridico-political orders of our time. Alalus thus becomes a category that carries Hegelian negativity, and a home for the idea of a potential subaltern (a coming one) that includes the animal and other entities such as assemblages of life and non-life (e.g., forests, rivers, mountains) without excluding human beings. It also questions the categories of the so-called human species and sub-species of taxonomy, that, I argue, still carry the epistemic presuppositions that once gave birth to scientific racism.

Pithecanthropus is no longer a valid scientific category, and the “archaic human” (a contemporary scientific designation) that the Dutch paleoanthropologist Eugène Dubois named as Pithecanthropus Erectus in honor of Haeckel, has long been considered to be a Homo Erectus. While the designation of Homo signifies a human, Homo Erectus is still seen as a paradoxical being-not-yet-man, and not too long ago they were described as a human species that lacked speech. Even the Neanderthals were thought to be without speech during most of the 20th century. They were thought to be so removed from humans that no relationship but war was deemed possible between the Homo Sapiens and the Homo Neanderthals. Such past-scenarios were imagined as an effect of the social/historical dimension of the “survival of the fittest” metaphor and due to the political context of the first half of the 20th century. In such an imaginary scenario, homo Sapiens appears to be a genocidal species that arose by eradicating all other human species and sub-species (or race) including the Neanderthals. This narrative of the Sapiens-Neanderthal relationship has long been debunked, as it is now well known that Neanderthals were not only capable of speech but possibly could speak at the same level as their contemporary Sapiens (Hillert, “On the Evolving”). It is also now proven that they have produced offspring with our ancestors and, as such, they themselves belong to an ancestral population that gave rise to contemporary humans.

Spear, the Neanderthal hero of Tartakovsky’s Primal, remains speechless until the last episode of the first season. He speaks at the very end of this season finale, and the first word that emerges from his voice is – Mira, the name of a Sapiens woman he fell in love with. Whether it is the T-Rex Fang or the human Mira, empathy and love seem to be what guide Spear in grasping a Universal language which is constituted by meaningless sounds and names, a language that makes him a comrade of Fang and the beloved of Mira. It appears that he was not speechless, but was not speaking in a human language simply because he had no human to speak to. He had no name to utter since the demise of his family. Not having any human speech until the very end of the first season, until the event of the manifestation of speech, still keeps him in the metaphysical category of Alalus, as not yet a speaker but who would end up speaking. But the word that emerged out of his voice was not a meaningful word, since it was a name (from a language that he did not know).

A name, even without meaning, has the paradoxical status of the most perfect human speech in the realm of theology, since names seem to be what constitutes Adamic language. And for Walter Benjamin, whether names have meaning or not is not what matters in the definition of Adamic names, which he also called the Universal Language. Rather, the nominating act itself designates the taking place of this universal language of men. In his own words: “Adam’s action of naming things … confirms the state of paradise as a state in which there is yet no need to struggle with the communicative significance of the words. Ideas are displayed, without intention, at the act of naming, and they have to be renewed in philosophical contemplation” (Benjamin, The Origin 37).

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. The Open; Man and Animal. Translated by Kevin Attell. Stanford University Press, 2004.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Translated by John Osborne. Verso 1998.

Hillert, Dieter G. "On the Evolving Biology of Language", Front Psychol, 2015.

Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. University of California Press, 2001.