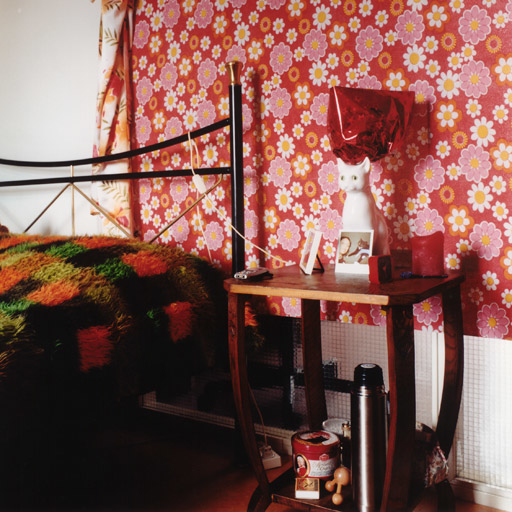

Investigating the line between private and public space has been a reoccurring subject in the work of Rabinovich throughout his career. As a newcomer to Holland, he was interested in the daily lives and homes of his fellow immigrants in Amsterdam. The photographs in the Apartments of Friends project (2005)1 embody a sense of duality. They have a certain quality of generalness that transports them out of the specific context and into a more general one. By photographing immigrant’s (temporary) homes he moves their interiors from the private into the public domain. Yet these interiors never lack the personality imparted to them by their inhabitants.This might seem strange when you consider that his photographs are often devoid of people. What can the photograph tell you, when you cannot see the protagonists? Rather than portraying them in the physical sense, Rabinovich chooses to suggest their presence through their personal belongings, which populate and personalize the home. The home is a shelter from the outside. No matter how temporarily one may live in a given space, it is human nature to surround ourselves with things that make us feel at home. We incorporate a part of our past into the present through our personal belongings, our pictures and cherished artifacts. By photographing these interiors Rabinovich affords us the opportunity to peer behind closed doors into the private space of the occupants. He offers us a glimpse of how these emigrants transform the dwelling into a personal domain. Rabinovich’s skillfully composed photographs have been on view in numerous public exhibitions adding a new, public context to these works with a personal touch. The picture is the beginning of the story; how it is read, lies with the beholder. Ayako Yoshimura described this aspect succinctly; reviewing the exhibition Non Places held at 66 East in Amsterdam-Oost in 2006, she noted that “The absence of a protagonist in the setting is enhanced by the sheer beauty of composition and light, which leads us to a distant memory; be it personal or collective.”

Another aspect that was particularly intriguing to Rabinovich was the Amsterdam phenomenon of the open curtain. In his artist statement Rabinovich explains: “I developed a fascination for the ‘open curtains’ phenomena, where one can easily view the private interior of people’s homes from the street level. In social conversations this served to present the locals as an example for how open-minded the Dutch people living in Amsterdam are. A ‘we have nothing to hide’ attitude that proved to be restricted and limited in what I could actually observe when I tried to focus on it.” Does the mental and cultural distance as a foreigner allow him a greater moral freedom to capture and record Dutch culture? Perhaps this is one of the reasons that he was selected for participation in the exhibition Becoming Dutch, held from May through September 2008 at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Posing the question “What does ‘Being Dutch’ or ‘Becoming Dutch’ mean in the 21st century?” The exhibition explored the notions of identity, nationality, citizenship and social cohesion. More than thirty artists were invited to exhibit their work; all dealing with the context or notion of foreigners assimilating into the Dutch Culture.

The open curtain phenomenon differentiates the city of Amsterdam from other European cities, shedding new light on the relationship between private space and the public sphere. The voyeuristic aspect intrigued Rabinovich, triggering him to investigate it through his photographic lens. He combined his in-depth knowledge of technical capabilities of a specific camera lens with his eye for composition and light, to achieve the desired effect. It led him to make the series of photographs Rear Window, consisting of carefully considered compositions captured with a telephoto lens.

The Rear Window photographs have mostly been taken in the evening by photographing from inside one home through or across the backyard into the rear window of the opposite home. You could say that these images were captured by a photographer who, located in one private home, bypasses the interstitial public space to penetrate and observe the private domain of the opposite interior. At first, this approach may seem to encroach upon the subject’s privacy. This series of photographs includes images of partially visible people in their homes, cooking dinner, watching television or carrying out some other daily activity.They are engaged with themselves in the comfort of their homes, completely unaware of our observant role. Through the window we can see part of their interior and part of the person. Just enough details to give our mind something to work with, but leaving sufficient room for our fantasy to fill in the rest of the story. It might seem as if we have penetrated deep into their personal space. Yet Rabinovich is careful to disguise the identity of the person and the setting in the photograph. He zooms in on his subject eliminating exterior details, which could help identify the location. This generic impression and effect is strengthened by a raster technique, blurring our vision even further. This conceals the details while adding an additional layer, creating a distance between the viewer and the image. Somehow we are kept at bay. As if to say: you may have a glimpse into this private space, but don’t get too close, the realm you behold remains in the private domain.

Our vision is impeded as we enter into Rabinovich’s installation where photographs in various sizes are scattered throughout a darkened room and are directly affixed to the surface of the black walls and floor. We embark with a small penlight in hand in search of the images, and the exhibition begins to take form. Through the darkness, we have the impression that we are peering inside the homes of unsuspecting residents throughout the city of Amsterdam at night. This voyeuristic aspect is intensified by the excitement of discovering another image on the wall, capturing yet another glimpse inside the private homes. We revel in the hope of uncovering the one detail which will disclose the identity of the person and specific location where the image was taken.

This intriguing and engaging work of Rabinovich is not only defined by his skilled photography techniques. The images are further enhanced by the chosen method of production - a silk screen technique on paper - and its subsequent display in the installation setting, in which the viewer is invited to participate. We crawl into the role and assume the eyes of the photographer, continuing the quest he initiated; to reveal what goes on in the private domain of an unsuspecting actor. In viewing the photography installation Rear Window one is transported into the active role of a voyeur.

Biography: Donna Wolf is the director of Déiska BV

en CV de Verzameling and is a Masterstudent Art

History at the University of Amsterdam

1. These photographs were commissioned for the exhibition:

Interieurs van een nieuw huis, april 2006 in the former home

of Anne Frank on the Merwedeplein in Amsterdam.

See also www.ilyarabinovich.com

A book was also published in conjunction with the exhibition:

Rabinovich, Ilya. ‘Interieurs van een nieuw huis’ (in:) Nauta,

N. e.a. Het Andere huis van Anne Frank: geschiedenis en

toekomst van een schrijvershuis. [exh .cat.]. Amsterdam:

Anne Frank huis, 2006. Amsterdam: Thoth, 2006: p.72-107