Q: Good evening! Would you like to introduce yourself?

A: Yes! My name is Iggy, I'm originally from Poland, and I just graduated from the Rietveld Academy after studying there for four years. I did the basic year, and then I studied in the Design Lab. Before that I did a Bachelor in Architecture in Copenhagen, but I felt that that wasn’t my path.

Q: And could you describe your practice as an artist?

A: I'm a visual researcher. My recent work ended up being a bit personal – a lot of it is inspired by how things work in my mind – how my emotional life functions or why I behave the way I do or why my body language is how it is.

My last projects were very much focused on visualizing needs through objects, like the need to self-soothe and the desire to fidget or stim. It’s a translation of unseen things into visual and material objects.

Q: Can you share something about your process, how you get from the idea to the finished project?

A: Most of my process consists of just thinking about the idea. It happens in my mind, almost as if I have no access to it. I think about something for half a year, and then I execute it like, you know, like this *snaps*, and that’s that. It’s something I want to work on, communicating my working process better, because a lot of important decisions about the work come as part of the process.

"Why do Hoodie Strings Taste So Good?" - Credit Ignacy Radtke

Q: Let’s move on to the work that you'll talk about on Monday, your book Why Do Hoodie Strings Taste So Good. Could you tell us some more about that?

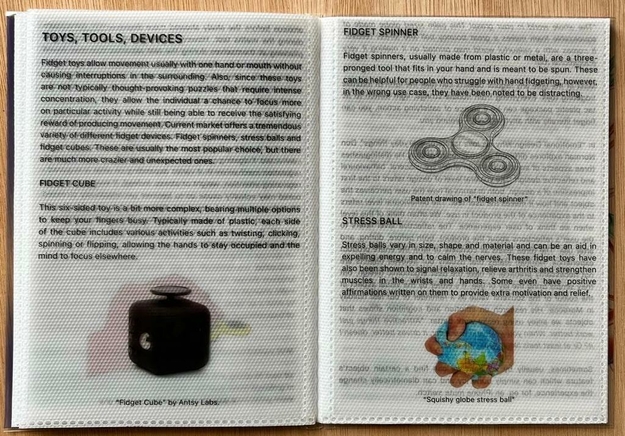

A: The publication is a mixtape of research on different approaches to fidgeting. It’s also about objects that visualize needs which are usually invisible or hidden.

I was wondering why I have this urge to constantly fidget with everything. Why are some of my senses more sensitive than others? So I was already analyzing my personal fidgeting world, and because I was studying design I wanted to focus not only on the psychoanalysis aspect of the research, but also on the objects themselves.

Q: Did your research have a specific focus?

A: I didn't focus on objects designed for a particular group of people, but kept it general, because everyone fidgets and everyone has their own way of fidgeting. I start at the very beginning, from being a baby. I was really intrigued that babies already suck their thumbs when they’re not even a month old. So there's lots about child development at different stages, which builds a bridge between infancy and later situations in life. Because even as adults, we still want to play. Though maybe we play differently. We don’t suck our thumbs anymore, but we use objects or tools or novelty items.

Even as adults, we still want to play. Though maybe we play differently.

Q: Can you give an example of that?

A: An interesting example would be what I call spontaneous vandalism. While people fidget, they often spontaneously destroy something, like a ticket to the cinema or a lottery ticket, or the tip of a pen…

Q: Yeah, I can relate to that! Pulling all the grass out when I'm sitting in the grass….

A: Exactly. It’s a very ambivalent situation because you really need to express this tension you have in yourself, to balance it out through an action, but then the action is deforming or destroying something. Whatever you have around you, you fidget with it, and you start to overuse it.

Spread from 'Why Do Hoodie Strings Taste So Good' - Photo by Ignacy Radtke .

Q: Have you received any interesting reactions to the project?

A: Yeah, I published it as part of my thesis and printed a hundred copies, which all sold out. And reactions have been pretty positive. Many people talk to me saying that they fully relate. They also tell me that the title is quite funny – with this kind of title it’s like when you know, you know, right? If you’ve never sucked on your hoodie strings you would have no idea what it’s about. But I realized that most people do relate to it, because everyone fidgets. And I thought yeah, we should embrace that rather than stop it or suppress it.

Q: One of the ongoing themes of our project is addressing the issues of care and accessibility in the art education system. As a recent graduate from Rietveld yourself, what was your experience navigating the (dis)comforts of art school?

A: I mean, my process of creating is pretty particular because I think about a project for a long time, processing it in my mind, which is of course only available for myself, and then after some time I just execute it. So there’s no process that’s visible to my teachers, and verbalizing the process was a big struggle for me. To them, sometimes it's the materials, objects or forms that speak for themselves. So I needed to work on making my process more visible, which was a challenge, and a big part of my education became learning how to communicate my process.

In my second year, I had a very big burnout, so I didn’t produce anything. I was in a very vulnerable, fragile state. I’m very happy that I wasn’t left behind by Rietveld and my programme. I had to get to the point where I could communicate enough to say, “Hey guys, I just won’t be able to produce anything because I don't feel like I can, but I still want to keep up studying and be in the same year.“ I felt that Rietveld was pretty open, particularly in my integrated program, and I had very understanding teachers in my department.

Q: What do you feel like helped to create this understanding?

A: There was understanding, but also instead of postponing it over and over, I made the decision to communicate clearly that I was not capable of producing work at that time. I think it helped to present them with the facts, that reality, so ultimately there wasn’t much they could say, it was either this or that.

Q: I think that actually leads into the next question we had, which was when you look back and reflect on that time in Rietveld, do you have any advice for students who might be experiencing similar (dis)comforts? I think, from what you've been saying, such a key point is not being afraid to voice your feelings and being really transparent about where you are mentally.

A: I think from my ADHD point of view, I often experience these periods when I feel very stuck, and very frustrated. With my ADHD, I experience more of an unregulated dopamine release in my brain, which has resulted in extremely low points and extremely high points. So sometimes even when you want to keep moving, it just feels like you’re stuck with your thoughts.

I think at these points, it's good to deeply analyze what's happening and be extremely honest about it with yourself. Always make sure to try to communicate and verbalize these things with significant others around you as well.

It’s about paying attention to what I do, accepting and embracing desires and needs like fidgeting, and finding a way to communicate them.

Q: Our final question is, how would you relate your artistic exploration to neurodivergence?

A: I think it relates because of my very analytical approach to things. It also has to do with a different way of paying attention. I think every part of life needs attention and requires a bit of understanding, everything from cooking your rice to brushing your teeth to making important decisions. In summary I would say it’s about paying attention to what I do, accepting and embracing desires and needs like fidgeting, and finding a way to communicate them.

To find out more about Ignacy's work, come and join his talk at our A/artist public event: Playing with (Dis)comfort, on Monday September 18th!