Welcome by Willem

Mediamatic's Director Willem Velthoven welcomed the audience and explained why Mediamatic’s A/artist project is developing this programme about neurodivergence in art education: “Our current estimate is that the percentage of autistic people in the arts is about ten times as high as in the general population. But many of us are very good at pretending we’re normal and spending a lot of energy on that, which means we sometimes don’t even find each other. This doesn’t put us in the best place to do what we’re good at - we want to change that, and we want to encourage art schools to facilitate that sort of change.“

Introducing Jenny

Willem then introduced our speaker of the evening, Jenny Konrad. Jenny is a long-term contributor to the A/artist roundtable discussion and has also spoken at the public A/artist event 'Sensing Self through Movement', presenting their graduation project 'Tailor Ourselves Towards'. They are currently researching sensory integration, alienation from our bodies in the digitised society we live in, and how we can de-alienate ourselves and understand our needs. For Jenny, this starts with understanding themself, a process for which they have designed various tools to help them.

Willem recounted a meeting during which Jenny pulled out their calendar and started to erase and fill in appointments. “I was really touched by it, it looked like a normal calendar but very carefully used“, Willem said. “So then Jenny told me it was their own design, which came from a path of learning to manage their own mind and practice. And I thought that would be really interesting to share.“

Jenny’s (artistic) history

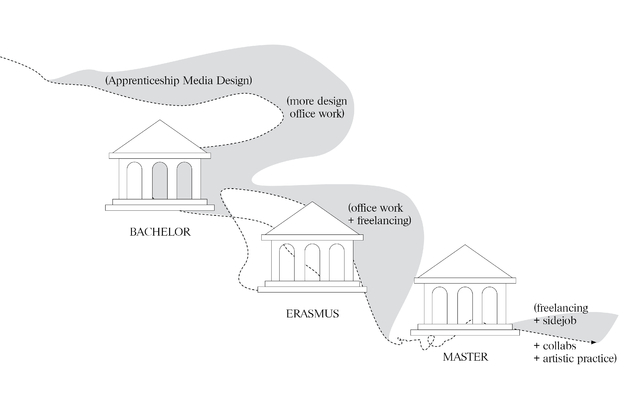

Originally from Germany, Jenny started their artistic career as a graphic designer after completing an apprenticeship in media design. Their experience with art schools includes completing a Bachelor in design in Düsseldorf, with an Erasmus exchange at ARTEZ in Arnhem, before moving on to a Master’s degree in Non Linear Narratives at KABK in The Hague.

“In the beginning many of my projects were kind of repetitive, iterative, algorithmic in nature“, Jenny said.

“At KABK my work started to become more physical, I started doing installation work that was also more socially engaged, and I did a lot of programming. Then I very slowly started to go a bit more into myself, before that all my work was very detached, but here I started to embrace myself a little bit in projects.“

“In this phase I was very focused on algorithms, which came from the realisation that my work was algorithmic - algorithms and AI became this very specific huge interest that I read everything about. I didn’t know why I was so interested, but you might call it my special interest at that point.“

“And then I got into autistic burnout.“, Jenny recounted. This happened during their Master, which coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic.

They defined autistic burnout: a “highly debilitating condition characterised by exhaustion, withdrawal, executive function problems and generally reduced functioning with increased manifestation of autistic traits, and distinct from depression and non-autistic burnout“.

“My brain wouldn’t tolerate anything anymore, I had increased meltdowns - I had had them before that, meltdowns and shutdowns, without knowing what they were.“, Jenny told us. This experience lead them to seek help and finally learn about their autism and receive a diagnosis, which has helped them a lot in how they navigate the world: “I always thought that it was just part of me, that I’m just wrong as a person. Through this burnout I realised that the problem wasn’t inside of me, there’s nothing wrong with me, I just have another neurology. And from there I started to figure out how to stop masking myself, what my needs are, and how I can get out of this.“

These new insights also caused a turn in Jenny’s artistic work, as they started incorporating more senses into their designs, going three-dimensional and using different materials to create haptic experiences: “I was trying to get out of my mind, out of the screen, more into my body.“

Jenny Konrad - Image courtesy of Jenny Konrad

Differences between art schools

Along the way, Jenny realised that the different art schools were supporting or not supporting them and their needs in very different ways.

“What I learned during my burnout is that analysing things is a strength of mine, so that is also my way of understanding my needs.“, they shared, and showed us a comprehensive table of the differences, positives and negatives of their experience at the three different schools.

For example, they mentioned the freedom to choose courses according to one’s own interests and to specialise according to ones wishes, which was possible in the BA programme, but not during the Erasmus exchange or the Master. Skipping classes or dropping courses was not an issue during the BA, but was noticed negatively during the Erasmus and MA. Mentoring was nonexistent during the BA, but was good during the Erasmus exchange and excellent during the MA. Assignments seemed to be narrowly defined at ARTEZ but were actually quite free, whereas there were much stricter guidelines for the methodology and timelines of assignments at KABK. They also pointed out periods at the different schools during which students were expected to focus on one project for an extended period of time. In Arnhem, this came in the form of a three-week period for one big project - “The best part of the whole year for me“, Jenny remembered - and in The Hague courses often incorporated five-day workshops, which similarly allowed them to go into hyperfocus for a week at a time. Jenny also remarked that in Germany, students often extend their studies by a semester or a year, which is seen as quite normal, whereas in the Netherlands extending studies is more of an exception and usually requires specific justifications.

Flourishing in art schools

Creating this table helped Jenny to understand which of these factors worked for them and which didn’t: “I need a more free selection of courses or courses that are more free in their content, short intense courses are great for my hyper focus, and skipping due to overstimulation needs to be possible - otherwise the pressure is just to high to always be on top with your energy levels.“

In addition to this, individual talks with the lecturer in another room helped Jenny a lot while overstimulated or under anxiety. “Sensory-wise it’s great if there is a space with the right lighting so you don’t have to sit under office lights“, they continued. They also remarked that extending one’s studies should be normalised in the Netherlands, since this would not only benefit neurodivergent students but relieve all students of the pressure that comes with having to complete a curriculum in a set amount of time.

“Of course that all still seems very utopian - my whole list seems very utopian. But I think utopia always starts with looking at one’s ideal needs.“

Jenny clarified that they shared these reflections in order to inspire conversation in the audience - “because maybe for you it’s completely different, and I think we need to be really open about and in tune with ourselves about what we actually need, rather than what we are told we need.“

Collecting neurodivergent experiences

After the break, Jenny shared some insights from a small survey they conducted among fellow graduates of their Master who are diagnosed or more or less tentatively self-diagnosed with autism and/or ADHD. “There is so much overlap between the two, a lot of times people have both of them or symptoms are overlapping. I don’t want to put this wall in between them because I don’t think it exists.“, Jenny explained.

They asked about other people’s experience with the structure of the programme and how they used calendars or other tools to organise their lives during this time. People identifying with the ADHD label mentioned a need for a To Do list to cross off tasks, as well as having multiple projects to jump in between and divide attention among. They also mentioned that while calendars are useful, it is also easy to forget to note things in the calendar or to look at it regularly.

For the people who were “leaning autistic“, issues that came up were difficulties with translating energy levels into an imposed schedule and trying to integrate periods of “mini hyper focus“ into their studies.

Jenny related to these experiences: “I can plan as much as I want, my energy levels just feel unpredictable.“ They explained that they developed their calendar and other tools in order to get to know themself better and therefore be able to better predict energy levels and make their schedule a little more flexible to accommodate their needs.

What do I need in order to flourish? How do I meet those needs?

Another insight people shared as part of the survey was that reflecting on these questions was difficult for them, since they did not pay close attention to their own needs during their studies. “You don’t learn to understand yourself, you just learn to view yourself through a neurotypical lens“, Jenny summarised.

Over the past years, Jenny has made an effort to break out of this mindset, and to become more attuned to their own needs in order to not only survive but flourish in their work and life.

They summarised the steps they took as follows:

- get to know yourself (journal, analyse and find pattern)

- embrace what works for you - especially when you learned it’s “weird“ or makes you a “failure“ - it doesn’t

- get people on board - a lot of times people are much more willing than you might think to help you to be the best version of yourself or be comfortable

- be kind to yourself - it’s super okay to be inconsistent. Journaling and keeping a calendar shouldn’t be a source of pressure or stress - it’s about enabling!

Tools for self-knowledge: Calendar

Finally, Jenny introduced us to their detailed calendar system, which they have been using and developing for three years.

The calendar is organised with a colour legend, colour coding deadlines and appointments, as well as different kinds of time: productive time, social time, self-care time and crip time.

“What is crip time?“, someone asked, and Jenny explained that they use it to indicate when they feel unable to “function“ due to their autism. Crip is being used by members of the disabled community as a reclamation of the term cripple, in the same way that the word queer was reclaimed as a term by the queer community. “I really like the word, so I’m using it.“, Jenny said.

The colour legend makes it easy for Jenny to parse how they spent their time in a given week. Work-intensive weeks will have mostly blue blocks, whereas weeks with a lot of social time will look quite orange. “I also need to make sure that there is enough yellow: self-care time.“, Jenny gave another example.

The calendar has a quarterly overview, a monthly overview, and a weekly overview. “I’m trying to make it very visual, so I don’t have to interpret and think a lot but can see visual patterns.“, Jenny explained.

In order to avoid having to strike through entries when plans change, which can lead to overstimulation, they use erasable coloured markers.

There is also space reserved on the pages for journaling and noting down ideas for activities, self-care, recipes and more, as well as to-do lists grouped by the tasks they contain, such as communication or finance. “Grouping similar tasks makes it easier to complete multiple ones in a row“, Jenny explained.

“This is the ideal way of using it for me, but it would probably be very different for other people.“, Jenny made sure to tell us.

Example weeks: Hyper-focus and social time

Jenny showed us a few of the weekly pages from their calendar to further explain how it has helped them understand themself better. Some weeks are almost completely filled with blue blocks - these are hyper-focus weeks, in which Jenny was able to really delve into one project. “Everything you read here is related to my project.“, they explained: “You don’t see anything below or on the side, not because I had nothing to do but because I was too hyper-focused to even think about it. But I got so much done in this week, I’d love to have this week again. I love hyper-focus!“

Another example stemmed from a week in which Jenny visited their family in Germany. “At the end of the week I had already had two meltdowns, and it was a holiday, so I thought that can’t be.“, they told us. Looking back at the calendar made them realise that the week contained a lot of orange: social time. “I didn’t realise before reflecting through my calendar that social time is great, but it’s also super demanding for me.“, they concluded, and added that the calendar works best as tool when used for both planning and reflecting.

“Do you have times when the pages are empty?“, someone asked, to which Jenny confirmed: “Absolutely!“, and started flipping through the pages to show us examples. “Sometimes it means I’m having a chaos week, other times it means I have everything in my head and just don’t need it.“ Either way, they have come to accept empty pages for what they are and not pressure themself to use the calendar in a fully consistent way.

Calendar conclusions

Jenny summarised the knowledge their calendar has helped them gain: The colour patterns helped them to understand what allows their brain to go into hyper focus. “If there are many different colours it’s more likely that I’ll feel burned out and overstimulated than when there are few colours filling many time slots.“, they summarised. Allowing time for hyper-focus is important, as well as planing everything in a steady rhythm, and grouping chores in thematic bulks in order to get them done more easily.

Tools for self-knowledge: Sensory Attunement

The second tool Jenny shared with us is one they dubbed “sensory attunement“. They shared a quote:

“Sensory regulation serves as the bedrock for various other self-regulation systems, including emotions, executive functioning and behaviour.“

“Based on this sentence I just try to understand: how is my sensory system.“, Jenny explained. - “What’s my sensory profile, which of my senses are more sensitive and which less, what sensory input am I craving, what am I avoiding…“

They incorporate these reflections into their daily life by keeping a Telegram chat with themself, in which they journal down sensory experiences at random moments during the day, prompted by alarms on their phone: “When the alarm clock goes off I try to make the time, even if it’s just half a minute - you get quicker and better at understanding yourself over time.“

Examples of sensory attunement

Again, Jenny generously walked us through how they realistically use this tool.

For example, when the alarm went off as they were sitting in a tram in the city center of The Hague, they journaled:

Symptoms of over- and under stimulation

“Every noise is so loud and too much and my heart is beating loudly. The artificial lights make me feel horrible. I feel slow, my short term memory is bad. I feel nauseous, like I need to throw up. I feel like crying, my ears are damp. I’m finding ways of hugging myself, like crossing my legs or leaning into a corner. I want people to stop talking and it makes me angry.“

Source of stimuli

“Crowded and noisy city center, people talking, artificial tram lights and tram noises.“

Affected senses

Auditory and visual, probably more senses affected but this is not about being perfectly complete, maybe it also smelled bad but not always doable to record everything.

Context

“It was in the morning, there had been no morning routine, crossing the city center, sitting in the tram. To add more context: I had enjoyable but busy last days.“

Actions that could have helped

In this case: put on a hat - “since my diagnosis I’m actually always running around with hats and it’s helped me massively“, Jenny added - and wear plugs, but they always hurt, so it’s a constant struggle of having a solution to a problem but it’s also a problem.

On other occasions this tools helped Jenny to realise that they had been sitting in the same position uncomfortably without eating or drinking for a long time due to hyper-focus, or that they were craving more stimuli such as loud music or social interaction. They noted that recognising bodily under-stimulation as well as overstimulation is an ongoing learning process for them.

Sensory attunement conclusions

Jenny summarised that the sensory attunement tool helped them realised that they tend to wake up overstimulated and need time in the morning to reset their nervous system by following a comfortable routine at home. Other insights included that they often struggle with artificial lighting and complex sound environments, whereas they found that they are often under-stimulated when it comes to touch and proprioception.

Jenny also mentioned that music helps them out of freeze mode when under-stimulated, and they have different stimming playlists for different situations - “They help regulate me pretty quickly, it’s amazing!“

Tools for self-knowledge: Signaling plan

The final tool Jenny showed us is a signalling plan they developed to categorise four (colour-coded, of course) stages of stimulation - “to see what I notice, what others notice, what I can do about it and what other people can do about it at the different stages.“, Jenny explained.“I figured out what I can do in the yellow phase, what I can do in the orange phase, and what I should avoid doing - once you understand this it just opens up a whole different life. I didn’t have a meltdown for a long time now.“

Wrapping up the evening: sharing is caring

With this, we reached the end of Jenny’s presentation. In the spirit of sharing is caring, they shared a QR code to their sensory attunement chart as well as the weekly calendar spread - open to personal adjustments, and of course for private use only - so that audience members could try them out for themselves.

They also encouraged guests to get in touch: “Especially if you’re working on any of these things yourself, if you’re working on the topic of stimming, the sensory environment, body de-alienation, disability justice movements I’m happy to exchange knowledge, meet, collaborate…“

I was impressed by Jenny’s open way of talking about their careful journey of self-discovery with a lot curiosity and compassion, and feedback from the audience confirmed that it was helpful and inspiring for many people to be shown these concrete tools with which to reflect on their own experiences and gain self-knowledge. With that, Jenny helped us take a step towards accomplishing what we set out to do with this series of events: dismantling the often still shameful or hesitant discourse around unmasking and voicing neurodivergent needs when it comes to navigating the structures of society at large and art schools in particular and sharing the wisdom and tools to do it.