This runs directly and impertinently counter to a trend that has been around much longer than our periodical. Mediamatic has grown from 48 pages to 144. From 190 to 500 grams. At the end of more than five centuries of development in which books have kept on getting lighter and cheaper. Gutenberg printed his first Bible in the middle of the 15th century. The monster weighed 22 kg. Since that time the book has continually become lighter. The price, too, has gone down.

The drop in price and weight made possible the explosive spread of the book. Thus you could say that the disappearance of the book made its spread possible.

The introduction of letterpress printing itself, however, was the first - and possibly the biggest - sacrifice in terms of quality. The printed book was merely a poor substitute for the lovely manuscripts of that time. Monks had always striven for regularity and perfection in the writing of their books. This effort lent their books, page for page, an exceptional quality. Gutenberg's invention produced a higher degree of regularity and perfection without no effort at all. Mechanical. Loveless. Cheap.

Concern over the frightful loss of our proud European book culture naturally did not extend to the people who could now finally buy a book for the first time. And others could now suddenly afford more books. Or, better yet, they saved so much on their Bibles that they could pay for a taller church tower!

Since then things have only gotten worse for the book, standard binding, machine-made paper, offset printing, paper covers, sewing, paperbacks, woody paper, laser printing, perfect binding. Books became so affordable and well distributed that people with less money and power, too, could publish them. A couple of centuries after Gutenberg, a whole new art form even arose: the literary novel. Everyone learned to read, and Europe developed culturally, intellectually and politically in an extremely prosperous manner. Thanks to the broad availability of cheap books. Thanks to the – partial – disappearance of the physical book.

But complaints about decreasing quality are still heard. That is the lovely thing about books: People have an extremely emotional bond with them. As soon as books look a little less healthy and well-fed, they immediately start to worry. The suggestion that the printed book will disappear completely thus usually leads to intensely emotional protests. The book lovers cry emphatically that books will never, ever disappear. And, of course, they won't. Books for book lovers will certainly continue to be made in the future. Books for readers, however, will become electronic in the foreseeable future. Not because readers do not like paper, of course. Nor because electronic books are better.

The reason for the disappearance of the printed book is economic. Electronic books are simply much cheaper. They cost so much less to reproduce and distribute that an electronic novel will easily be sold for 20 percent of the price of a paper novel. Four-fifths of the price we pay for books goes for paper, printing, binding, warehouses, distribution centres, cargo transport, bookstores and other things that have nothing to do with content.

As soon as electronic text readers are a generation further along, we will have to choose: the new Amis on paper for forty guilders or the new Amis digitally for eight. (After all, writers and publishers will earn more if we choose for digital...) From that moment on, book lovers will pay more and more for well-made books which will be published in smaller and smaller print runs and thus end up in a vicious circle of rising prices.

Digitally distributed literature will be sold in a manner resembling that of video games or Web sites. Everyone will be able to download the first chapter to see if they like it. After that, you choose whether to pay a few guilders for the rest, or maybe to read it free with ads in the margins. You will probably also still be able to order the new Amis on paper. His print runs are so big that one-tenth of the usual stack of books will still be economical to produce. Authors who don't sell as well, though, will soon no longer be printed.

Rocketbook and Softbook, two electronic readers from 1998. They still cost a bit too much, but they already work well. They have easy-to-read screens, they are very easy to operate, you can make notes, the batteries last a long time, they don't weigh much and tou can get your books directly from the publisher via a telephone line.

Lovers of books will deplore this, while lovers of literature will applaud it: reading will be cheaper and the threshold for publishing a text will become lower because there will be no need to invest in print runs. Culturally, in any case, it will be exciting. The mass use of interactive media will lead to new cultural forms. As the spread of cheap books gave rise to the literary novel, so too will the spread of networked interactivity accommodate great cultural developments.

It may take a decade before the situation sketched above becomes reality. For us, however, the moment has come.

Mediamatic has long reveled in its love for the book. Now, though, the time has come for us to definitively cross over to the digital format for articles and reviews. You will find us at www.mediamatic.net. After all, we have had more readers on our outstandingly well-visited Web site than on paper for a couple of years already... Starting now, we will use the energy we have been putting into the paper version to further develop the online version of Mediamatic.

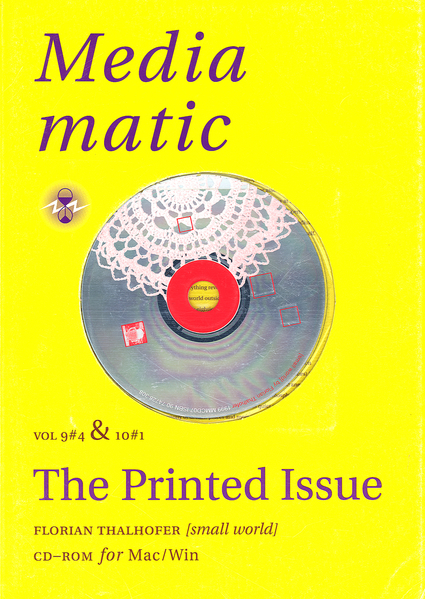

We will also continue with the physical distribution of cd-roms and, in the future, dvds. The cd-rom will probably be done away with sooner than the printed book. Good works for cd are being made at this moment by a growing number of artists and designers. We will continue to select and distribute that work by subscription and in single copies.

After a couple of generations we will look back in amusement at all the material that was wasted in the second millennium.

Translation: Laura Martz